The Earth’s cryosphere—its frozen landscapes comprising glaciers, sea ice, permafrost, and snowpack—forms a crucial pillar of global climate stability and water security. In 2024, the United Nations General Assembly set the stage for a transformative decade—2025 to 2034—as the Decade of Action for Cryospheric Sciences. This bold initiative calls on scientists, policymakers, financers and communities worldwide to work together and explore, understand, and address risks posed by a rapidly changing cryosphere.

Changes in glaciers, permafrost, sea ice, and snow cover affect our everyday lives deeply by altering water supplies, damaging infrastructure, and reshaping local economies and cultures. Global collaboration, innovative research, flexible financing, and community engagement will be our tools for adaptation and resiliency in the coming years.

This article explores the intersection of glacier financing, broader sectoral cooperation, and the critical role of cryosphere science in fostering resilience amidst socio-economic and environmental uncertainties.

Breaking the ice

The cryosphere occupies only 15 per cent of Earth’s surface, but it is vital to global climate change adaptation and mitigation. The polar ice sheets store most of the planet's freshwater, mitigating sea-level rise and extreme weather events. Mountain glaciers and seasonal snowpacks serve as freshwater reservoirs for billions of people. Permafrost, rich in stored carbon, acts as a regulator, preventing methane and CO₂ emissions that could irreversibly accelerate global temperatures.

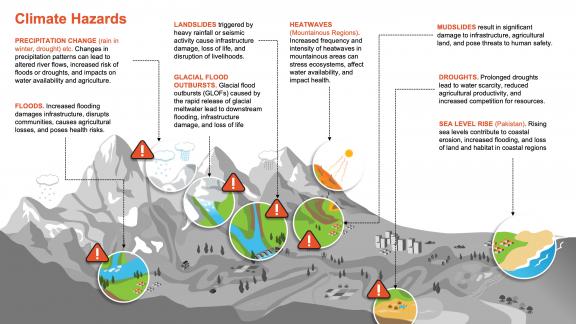

Source: Asian Development Bank

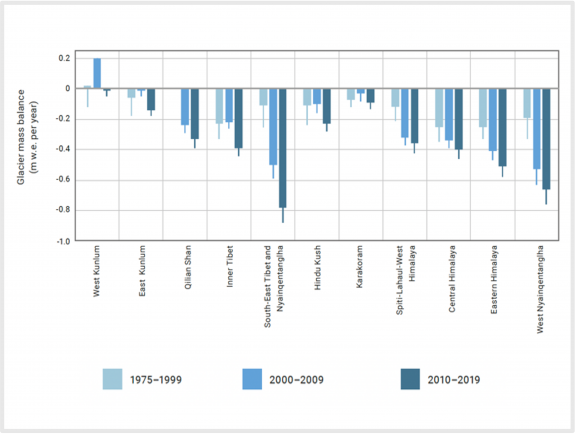

The socio-economic interdependencies are equally profound. For instance, glacial meltwater sustains irrigation for farming communities across Asia’s river basins, while energy production in regions like the Andes relies on consistent snowmelt. Glaciers retreat, risks like glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), critical infrastructure destabilisation, and water scarcity threaten local communities and economies alike. The Hindu Kush Himalaya region could lose up to 75 per cent of its glacier volume by 2100. Meanwhile, Arctic permafrost thaw could release USD70 trillion worth of climate damage. These threaten global water security, agricultural systems, and coastal communities.

Glaciers in the Hindu Kush Himalaya region are melting faster than the global average. Source: UNESCO, 2025

Cryosphere projects face persistent financing challenges. Current estimates show that only three per cent of global climate finance reaches mountain regions, while less than one per cent of adaptation funding specifically targets glacier protection. Infrastructure costs in mountainous areas typically run 30-50 per cent higher than lowland projects, creating significant barriers to investment. Traditional funding models struggle to capture the true value of cryosphere services, leading to chronic underinvestment in these critical systems. A systemic approach recognising cryosphere-water-energy-ecosystem interconnectedness is urgently needed.

Global water governance and collaborative cryosphere solutions

A major barrier to scaling cryosphere financing is coordination across fragmented stakeholders. Cryospheric regions often span countries with diverse political and socioeconomic conditions. The challenges of funding adaptation measures such as glacier lake outburst flood (GLOF) risk management, transnational water governance, and sea-level rise preparedness underscore the necessity for both private and public investments.

Cryosphere preservation demands global collaboration by integrating local efforts with international frameworks. Aligning Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6.5 on Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), the Paris Agreement for climate action, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework provide a cohesive approach for addressing cryosphere-linked water governance challenges.

A GCF-funded project implemented by UNDP and Pakistan’s Ministry of Climate Change & Environmental Coordination will protect vulnerable communities in Northern Pakistan from glacial lake outburst floods through early warning systems, infrastructure and disaster management policies. Photo: UNDP

Innovative financial mechanisms for cryosphere conservation

Innovative financial mechanisms for cryosphere conservation must integrate efforts across governments, multilateral development banks (MDBs), private investors, and concessional financing. MDBs play a pivotal role in de-risking investments through blended finance, which combines public resources with private capital to fund cryosphere projects. Crowdsourced private capital could tie returns to successful glacier restoration, enabling investors to directly support cryosphere recovery. Additionally, blended finance models can fund large-scale, high-impact mitigation and adaptation projects, combining private risk appetite with concessional funds. Expanding these mechanisms requires robust data-sharing platforms, policy and regulatory support, phased investment models, and better quantification of cascading benefits, ensuring that cryosphere conservation becomes a mainstream priority within green finance portfolios.

Recommendations and way forward

Bridging the financing gap requires a multi-pronged approach, shifting from project-based to systemic funding approaches that recognize the interconnected nature of cryosphere systems using innovative financing models. Public-private partnerships, green bonds, and climate funds can mobilise the necessary resources for research, infrastructure adaptation, and community resilience.

Clear, evidence-based communications about the irreversible nature of cryosphere loss and its profound impacts on water security, infrastructure, and livelihoods will stimulate urgent policy action. Together, these strategies establish a foundation for transformative action that bridges the gap between finance and the pressing needs of a changing cryosphere.

The upcoming Decade of Action presents a unique opportunity to revolutionise how we finance cryosphere protection. With estimates suggesting that USD100 trillion in climate finance will be needed by 2050, ensuring that Earth's frozen assets get their fair share is crucial. This will require unprecedented collaboration between governments, financial institutions, scientists, and local communities.

By Bapon Fakhruddin, Water Resources Management Senior Specialist, GCF

Acknowledgement: The author would like to thank the UNESCO brainstorming session on 20 March 2025, in Paris, to shape the vision and milestones for the Decade of Action.